The Waring School’s Brickwolves Robotics Team developed a Student Carbon Calculator Curriculum to empower students with information about embodied carbon

by Charlie Pound (8th grade), a member of the Waring School Brickwolves, a team of 14- and 15-year-olds participating in the First Lego League (FLL) global STEM competition

“As I stood outside the Massachusetts State House in Boston at 11:30 a.m. on a Friday morning, I looked around at a large crowd of students and other young people holding signs.” This was how Olive Sauder, member of the Waring School Brickwolves, described the global student climate strike on September 20, 2019, which was inspired by Swedish activist Greta Thunberg.

Nearly every member of our robotics team attended the climate strike, and we were surrounded by two-thirds of the Waring School’s student body. Over 6,000 like-minded students from other schools joined us, taking a day off to protest government inaction on climate change at the state and federal levels.

Waring School Brickwolves team members at the Boston Climate Strike

Speeches began and went on for almost two hours. During the speeches, it struck the Brickwolves who attended that although the speakers were clearly passionate about climate change, they did not emphasize scientific data or specific solutions that would have made their case for policy change more convincing. “The speakers focused on classic images of climate change: inefficient transportation and big factories, while in reality, those aren’t the biggest contributors to climate change” said Olive. For example, creating and operating buildings is responsible for 40% of all annual worldwide greenhouse gas emissions, but the speakers at the climate strike did not mention it.

If students want to effectively lobby the government to take action regarding the environment, they need to be able to use convincing facts and the right vocabulary to ensure that adults in a position to implement changes will listen to them. Our robotics team realized that we could empower youth, giving them the specific data and knowledge they need, through our Innovation Project.

The Waring School Brickwolves is a FIRST Lego League (FLL) robotics team. FLL is the largest robotics competition in the world, with 38,800 teams and 310,400 participants. As part of the annual competition, each team completes an Innovation Project related to that year’s theme.

The theme this year is “City Shaper,” in other words, a focus on city planning, buildings, and construction.

At the start of the season, inspired by the global student climate strike, we thought in somewhat vague terms about doing a City Shaper project aimed at helping the environment. We were also inspired by the fact that our school, the Waring School in Beverly, Massachusetts, is constructing a new building designed to be extremely energy efficient. This provided a perfect opportunity to study how buildings impact the environment.

Our team at the State Championships. From Left to Right; Owen Cooper, Francis Schaefer (coach and physics teacher), Peter Hanna, Adam Madeja, Charlie Pound, Olive Sauder, Amelia Wyler, Chris Douglas, Collin Keegan, Sarah Carlson-Lier (coach and school librarian)

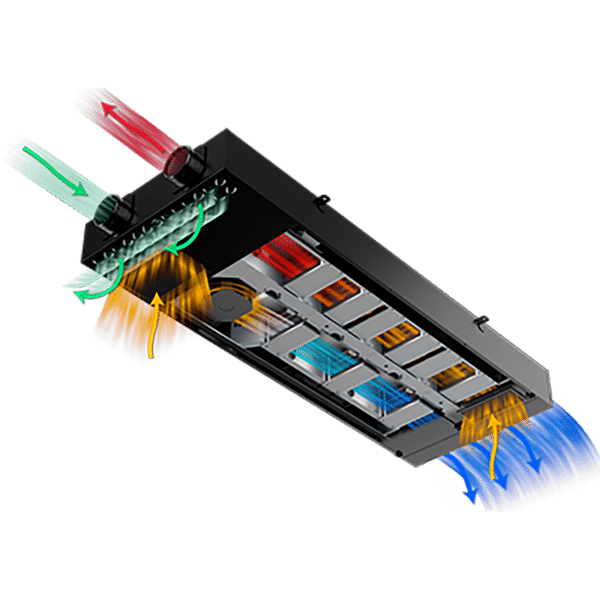

We learned that our planned school building, expected to open in December of 2020, is designed to meet a sustainability standard called “Passive House.” This standard is the most rigorous sustainability standard in the world and requires the building to use 9 times less energy than an average building. It also requires that the building be virtually sealed to prevent heat loss. Our school will be the first high school in New England to have a Passive House school building.

We were excited about this idea because it would educate students about general ideas of embodied carbon, construction, and greenhouse gases while making the issue personal and close to home by focusing on schools.

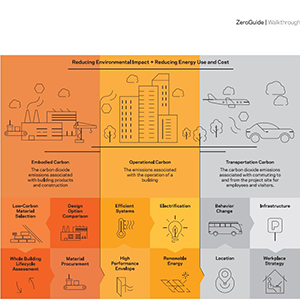

With the help of one of our teachers, we contacted the architect working on our new building, Tim Lock, to jump start our project. Tim is the principal architect at OPAL, a leading Passive House firm for commercial-scale projects. During our interview with Tim, he told our team that Passive House is the best standard to lower the operational carbon of a building. He explained that operational carbon is the carbon that a building emits due to lights, appliances, heating, cooling, and other electric items. However, he also pointed out that Passive House doesn’t address the other 50% of the carbon emitted over the life cycle of a structure, which is called embodied carbon, the emissions associated with building construction, including extracting, transporting, and manufacturing materials.

A rendering of the New Passive House Building at Waring School.

Tim Lock told us that embodied carbon accounts for about 20% of global emissions yearly and is mostly ignored by companies and governments because it is so difficult to calculate and address. Embodied carbon is hard to measure since it requires advanced knowledge and expensive software to complete what is called a Whole Building Life Cycle Assessment (WBLCA). WBLCA is an optional add-on to popular architectural applications, but can be confusing to use and requires advanced knowledge of architecture and 3-D Design. It would be challenging for a middle school or high school student to understand the challenge of reducing embodied carbon by using such a tool.

We spoke with another architect who had been designing schools for 30 years. He had never heard of embodied carbon or the Passive House standard.

Charlie Pound

Creating and operating buildings is responsible for 40% of all annual worldwide greenhouse gas emissions, but the speakers at the climate strike did not mention it.

We imagined students walking around their school, taking measurements, and seeing their school in a new way. We also wanted them to obtain data and numbers about their school’s embodied carbon from the SCC to empower them with information when they spoke to adults about the issue. Finally, we wanted the calculator to give students specific ways to improve the carbon footprint of their school buildings.

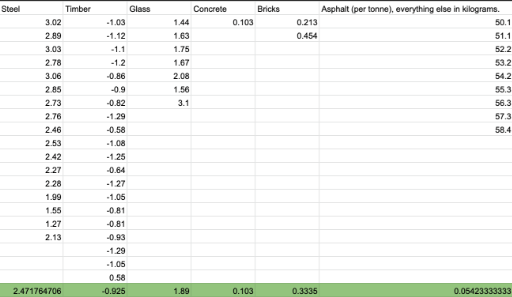

With the help of Suzanne Strahl-Cooper, an expert web developer who is also Owen’s mom, we began to code our idea into reality. We needed to integrate some key data, including values for embodied carbon emissions of typical building materials. We were very relieved when team members Collin and Chris came running into our work space ecstatic that they had found the Inventory of Carbon and Energy (ICE) database, published by Circular Ecology, an organization at the University of Bath in the UK.

After hours of looking through the ICE database, we found the numbers that we needed.

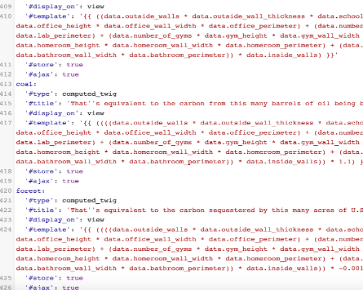

Using values we found in the ICE database, we created a form asking students for specific measurements of their school building, such as the square area of the building, room perimeters, materials, and the thickness of walls. We coded a complex math equation to calculate the embodied carbon using values and numbers from the ICE database. We worked long hours learning how to code in a sometimes chilly conference room, but felt proud as our ideas began to transform into reality and we understood the intricacies of how the code behind the calculations worked.

The code behind our Student Carbon Calculator

We got the SCC finished just in time for our first FLL tournament, the Revere Qualifying Tournament. We won first place partly because the judges loved our software application – the SCC. They said our project was “super robust” and was “empowering others.” Winning the qualifying tournament gave us a chance to compete at the state championship competition in Newton, Massachusetts, which meant we had to scramble to improve our project.

In the week between the two tournaments, we met with Sam Hoyo, the director of sciences for the Arlington school system. She helped us identify how a curriculum based on the SCC might fit into the Massachusetts Education Frameworks, the guidelines for courses in Massachusetts’ public schools. She then helped us craft the outline for a 30-day Project Based Learning curriculum on embodied carbon using our SCC. We got it done just in time to head off to Newton.

Suzanne Strahl-Cooper and Charlie Pound working together on coding the Student Carbon Calculator.

Owen and Chris preparing our robot at the State Championships. (Photo courtesy of the LigerBots)

The judges called our Innovation Project “an innovative solution that will make a difference”.

With the help of Arlington school principal Mike Hanna, who is also Peter Hanna’s dad, we determined how to design a more developed embodied carbon curriculum around our calculator. However, there were almost no resources to pull from because no one else had done what we were trying to do.

As far as we can tell, embodied carbon has not been a subject that schools teach. That is exciting, because it means we are likely one of the first to create a curriculum on the subject.

However, it’s also hard because there are few materials about embodied carbon that are suitable for students for us to use, borrow from, or reference.

Mike Hanna working with Peter, Olive, and Chris on editing the Curriculum.

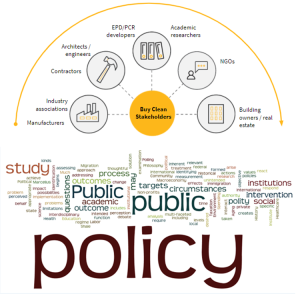

About a week after we qualified for Worlds, Andrew Himes, a former Microsoft executive and program specialist for the Carbon Leadership Forum, found an online article about us in the Gloucester Times, a local newspaper. As an activist who is passionate about reducing embodied carbon, Andrew reached out to us to offer his congratulations as well as his offer to help. During our first video conference with Andrew, he talked about the mission of the Carbon Leadership Forum to dramatically reduce embodied carbon through research, education, and action. He was very supportive of our curriculum and offered to read it when it was ready.

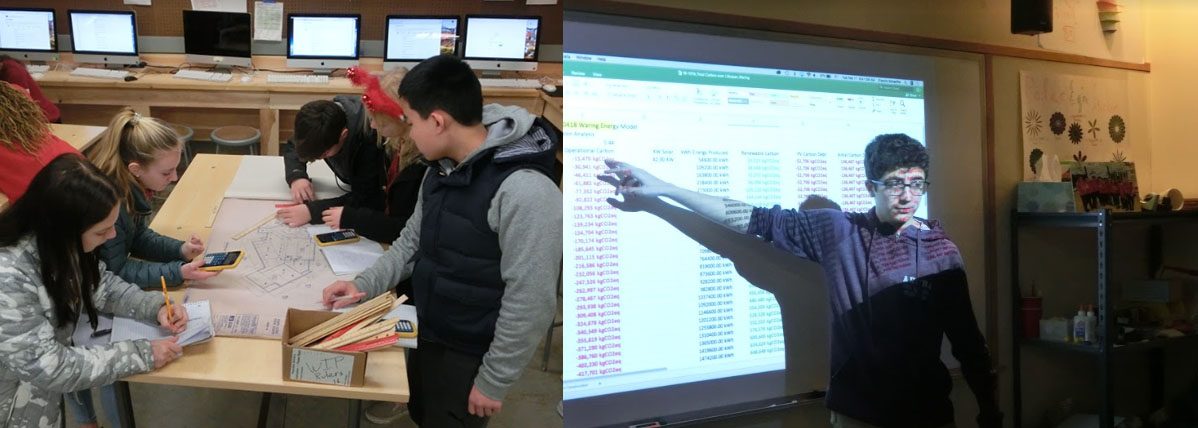

After many hours of hard work, we sent the first draft of our curriculum off to be critiqued by Mike Hanna, and we asked one of the teachers at the Waring School to run a condensed version of our curriculum in his 8th-grade science class. We thought we had better test it out!

It was an incredible experience seeing my teammates teach a subject that they knew so much about and had spent so many hours preparing for. I was very proud of them.

I was forbidden to answer questions for the first couple of classes because I had helped with creating the questions. So, sitting quietly, I enjoyed seeing the whole class begin to understand embodied carbon and use the SCC. I saw our hard work pay off as the first group of students learned about this important subject.

Chris Douglas, one of my teammates who helped teach the class said, “After putting in all this work creating a curriculum it was really amazing to see it go from something theoretical to actually being used to help educate students and impact them in a positive way. The prospect of actually teaching a course to people you know who are less than a year younger than you seemed pretty absurd at first especially since I had never taught before.”

After the SCC was tested in my science class, the students and the teacher gave us valuable feedback on how to improve the SCC and the curriculum. For example, they saw that we had forgotten to include the embodied carbon of a building’s foundation. They also found a lot of spelling mistakes!

Chris Douglas and Olive Sauder, members of the Waring School Brickwolves, teach the ten-day version of our curriculum.

Currently, we are working with another school in Arlington to see if they are willing to run our 30-day curriculum in science classes. We hope to present our ideas to them in the next couple of weeks.

Andrew Himes and Kate Simonen not only gave us valuable resources for our curriculum and introduced us to many new concepts, but they are also considering hosting our curriculum on the CLF website. This would allow our work to be seen by people all around the world and would spread the use of our calculator farther than we had ever imagined. Without such help from the CLF, our project would only include the robotics competitions, which end after this year. Hopefully, with CLF’s help, we will be able to spread our curriculum all around the country, and maybe even beyond, so that it can be used for many years to come.

We hope that the next time our team members attend a climate strike, we will see students who have taken our course and are empowered by what they have learned about climate change and, in particular, the important, but underappreciated, role of embodied carbon. We hope to hear them speaking armed with specific data and information so that adults will be forced to listen.

Owen and Chris preparing our robot at the State Championships. (Photo courtesy of the LigerBots)